Free speech during COVID-19

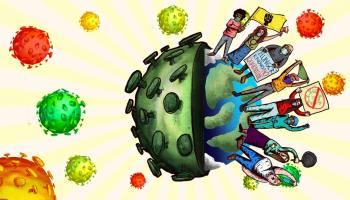

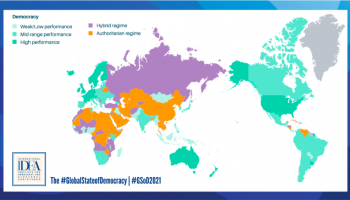

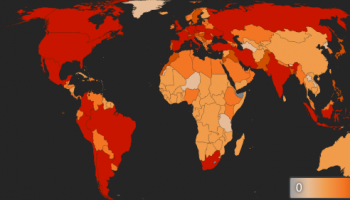

Over the past few years, states around the world have passed increasingly restrictive laws and regulations controlling the media and online content—essentially deciding what is safe for people to consume versus what it considers “fake news.”

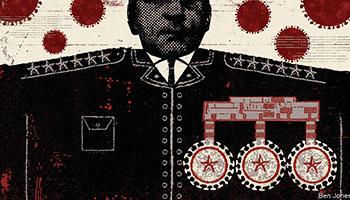

This trend has intensified during the pandemic, which has provided leaders in more autocratic states political cover to rush through legislation suppressing independent media and dissent. The World Health Organization has labeled the spread of bogus news on the outbreak an “infodemic.” And “fake news laws” have given states powers that may long outlast the pandemic—and serve to weaken public trust in media, giving governments control of the narrative.

Social media platforms, particularly Facebook, have increasingly regulated content posted by all media outlets. Despite Facebook’s claim that it is “ensuring everyone has access to accurate information and removing harmful content,” an international survey voted the platform the biggest spreader of misinformation. As this content is widely available and accessed by such a large global audience, it begs the question of how nonpartisan a platform can be—and whether censorship can ever be “good.”

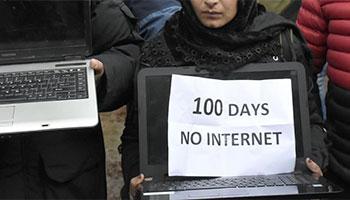

During the pandemic, women and other marginalized groups have enjoyed greater participation in conferences and webinars because most events have been taking place online and don’t require travel and associated expenses. However, internet shutdowns have also negatively impacted these groups, especially those in rural areas with limited access to internet. Since January 2020, at least 13 countries have imposed internet shutdowns that have seriously impacted people’s ability to access information on the pandemic. In the Bangladesh refugee camp Cox’s Bazaar, internet restrictions led to rumors and the spread of false information, which experts say contributed to a lack of awareness and impacted the ability of international agencies to respond swiftly to cases.

A free and independent media is essential in holding governments accountable for their handling of the pandemic. Freedom House’s annual study of internet freedom around the world “Freedom on the Net” found that in at least 45 out of 65 countries covered, activists, journalists and civic actors were arrested or criminally charged for online speech related to COVID-19. In Malaysia for example, journalist Wan Noor Hayati Wan Alias is facing up to six years in prison for what the government considered “causing a public panic” following her report criticizing the government’s decision to allow a cruise ship with Chinese tourists to dock in Penang.

Although populations have faced unprecedented restrictions in the last few months, groups have been finding new ways to organize and demonstrate. In April 2020, for example, Palestinian feminists organized balcony protests in solidarity with victims of domestic violence. We’ve seen in Zimbabwe how songs and music has been used to engage the youth to put pressure on authorities, and also how online campaigns have been encouraging citizens to engage and raise awareness.

Some examples of restrictions to free speech we’ve seen are:

- In Nicaragua, many critical journalists and media have been targeted after questioning the government’s handling of the pandemic and official Covid-19 figures

- In Turkmenistan, where the government continues to deny the existence of Covid-19 within the country, the authorities have detained and intimidated those speaking out about Covid-19 related issues in public places, including doctors.

- In Turkey, the government has used the pandemic to further crack down on journalists and citizens. Journalists have been jailed, charged with causing panic and for publishing reports on coronavirus outside the knowledge of authorities.

- In the Philippines, the government has taken advantage of the pandemic as a distraction to pass legislation that threatens free media, such as shutting down ABS-CBN; the leading broadcast company in the country.

Our recommendations

- Individuals can verify the accuracy of online content. These fact-checking resources are helpful tools: First Draft, which allows you to search for information in over 20 languages; Twitter’s coronavirus fact checking tool; Raven Pack, which verifies trends and media exposure to coronavirus.

- Reporters Without Borders (RSF)’s #Tracker_19 is documenting state censorship and misinformation; the International Press Institute’s Covid-19 tracker is monitoring attacks on journalists and the press worldwide.

- Individuals and organizations must find ways to continue to organize and demonstrate effectively and safely. See examples here.

COVID Report: Year One

One year into the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on civil space are increasing. Recognizing the need to protect public health, our report looks at nine kinds of restrictions that could limit civil space for the long term and how civil society can respond.

Regions currently impacted

Get in Touch

Under the Mask is an evolving project dedicated to the alarming increase in restrictions on civic space around the world, worsening during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how individuals and organizations are responding to protect that space. We welcome your feedback about this website, and we invite you to participate in this collective effort.